On Cognitive Flexibility

Can Preschoolers Think About Something In More Than One Way?

So, last week all of my Google alerts went off. I have Google alerts set up for when someone is citing two specific journal papers that I heavily relied on in my research (to make sure that I know immediately if someone is doing exactly the same thing as I do), and a couple more alerts about children and cognitive flexibility–my area of research. I never had all of these alerts go off at once, so, naturally, I panicked. Then I went to have a look. My Ph.D. dissertation was published online. I set off all of my alarms. So, I figured, it’s time to write a post about my research.

I studied cognitive flexibility, which is the ability to think about something in more than one way. With preschoolers we typically mean to think about a picture (or several pictures) in terms of shape and colour (and sometimes size). The most widely used task to measure this skill with preschoolers gets them to sort blue rabbits and red boats into two boxes, one with a blue boat and the other with a red rabbit on top of it. First we ask them to sort the cards by shape (all the rabbits go here, and all the boats go there), and then we tell them to sort by colour (all the blue ones go here and all the red ones go there). Three-year-olds almost always keep sorting by the first dimension–they can’t make a switch from thinking about the pictures as rabbits and boats to thinking about them as blue and red ones.

My research focused on concurrent cognitive flexibility. I tried to get preschoolers to coordinate both colour and shape at the same time. There are some tasks that have been used with preschoolers before, and the kids typically fail them until they are about 7 years old (in 2nd grade, or Year 2 for the Brits). So, naturally, I tried to get 3-year-olds to do that. And they did, to my considerable surprise. You see, what happened before was that the tasks that researchers used included all kinds of other demands, that actually tapped into other skills, such as abstraction (figuring out which dimensions are relevant). Turns out, when you ask kids to give you the red circle, they almost never give you the blue circle, even though they could. Even 3-year-olds are pretty good at distinguishing the small red stars from the big red stars (and from the small yellow stars, and the from the small red triangles), indicating that they at least notice all the dimensions.

This is the main thing I found. My second “big” finding is rather nit-picky, but that’s what Ph.Ds are for. Because previous research found that kids are unable to coordinate two dimensions simultaneously (think about both the shape and the colour of the red circle) until they were about 6 or 7 years old, it created the feel that first children have to figure out (or learn; my research did not focus on the nature vs. nurture debate) how to switch between two dimensions, and only then can they coordinate these two dimensions simultaneously. So, it seems that concurrent cognitive flexibility (coordinating two dimensions simultaneously) is really just a more advanced switching cognitive flexibility (thinking about two dimensions, one after the other). My second “big” finding is that this is probably not the case.

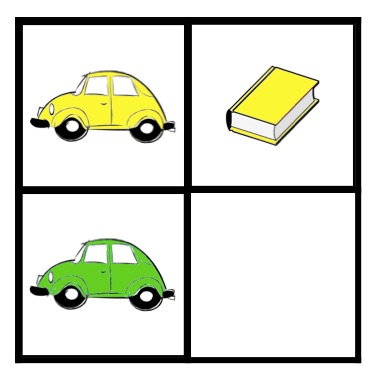

If both cognitive flexibility types are the same process, we would expect certain factors to affect them in the same way. For example, take the “labeling” factor. In both the tasks I mentioned before, I tell the kids which dimensions they should pay attention to (“the blue ones go here”, “give me the red circle”, and so on). I could ask them to first figure out which dimensions are more important, and only then to coordinate these two dimensions. This results in all kinds of awkwardness when talking to a 3-year-old, such as “these two go together in one way, and these two go together in another way”. However, the interesting thing is that when I ask children to switch, say, from thinking about the colour of the blue rabbit to the the shape of the blue rabbit, telling them which dimension to pay attention to helps them do it. It makes it easier to pay attention to the dimension that is relevant now. Then I asked them to coordinate two dimensions simultaneously by completing a 2x2 matrix like this one:

Turns out that, in certain cases, kids find it harder to complete this matrix (that is, to choose the green book from an array that includes also a green car, a yellow book, and a yellow car, among others) when I tell them that “all the cars go on this side and all the books go on that side”, than when I don’t use labels such as “books” and “cars”. I have some data that shows that it’s more difficult for them because it makes them focus only on one dimension–the one I labeled last–which is exactly the opposite of what we want them to do. As I said, this is a bit more nit-picky, but it suggests that switching between two dimensions and coordinating two dimensions simultaneously are two different processes.

What Does This Mean?

Well, there are all kinds of implications, but the truth is that we really don’t know. The ability to coordinate two dimensions simultaneously in preschoolers has not been studied very well. It could mean that we can use the difference between the two skills to predict different things. For example, it could be that switching between two dimensions predicts academic achievements, whereas coordinating two dimensions simultaneously predicts creativity, where you need to find connections between seemingly unconnected things. On the other hand, it could mean that the kids where I collected the data are particularly weird in some way. It all depends on what other researchers find if they look into preschoolers’ ability to think about something in more than one way. In other words, like all good science projects, this project raised more questions than it answered, which is why I LOVE being a researcher.

Keep asking questions! ![]()