Can Preschoolers Think of Something in More Than One Way?

I started working on my PhD research almost 10 years ago, in September 2007. Some of these years I worked on the research full-time, some of the years only part time. I took two years off (one for each kid), and another summer term when we moved to the UK. Even without going on part-time adventures, research takes a long time. You don’t always get the answers you are looking for. You go off on tangents and side-paths and dead-ends. Then, when you do have something that works, what you thought you’d get is almost always inconsistent with what you actually get. This is one of the reasons I love being a scientist and a researcher. Research—and particularly researching child development—keeps you on your tows. All the time. Kind of like a long ballet class—you gotta work hard and you will fall down, but when you get it right it feels and looks amazing.

Last week was one of those times that feels amazing. A paper I wrote based on my PhD research was published with the Journal of Experimental Child Psychology, which is a well-respected, peer-reviewed academic journal. It’s a mark that other researchers find my work interesting and up to quality scientific standards. It’s a gold star for scientists. So today I’ll talk about this paper, and I’ll try to be as objective about it as I can.

What We Did

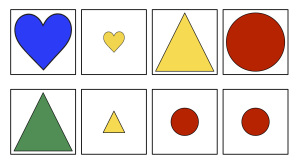

This paper describes a task that we developed in my lab, for the purposes of my PhD. You remember I wrote about cognitive flexibility (which is the ability to think about something in more than one way), and about how most of the research looking into preschoolers’ cognitive flexibility asks children to think about something (say, a blue rabbit) first in one way (say, as a rabbit) and then in a second way (say, as a blue thing). And how I was interested in getting preschoolers to think about something as both blue and a rabbit at the same time (we called it concurrent cognitive flexibility). So we developed (which is the scientific term for “made up”) this task called the Multidimensional Card Selection Task in which we basically asked kids first to select all the hearts, then to select all the yellow triangles, and then to select all the small red circles. There’s a picture below of the cards we showed them. You will note that when we did that, we actually got them to think about the cards they need first in one way (shape), then in two ways at the same time (shape and colour), and then in three ways at the same time (shape, colour, and size). We assumed that 3- and 4-year-olds would not be able to do this, and only closer to their 5th and 6th birthday would kids be able to think about something in three different ways at the same time. So we ran this task (and a bunch of other tasks) on quite a few 3- and 4-year-olds to see what they do.

What We Found

We found, to our utter surprise, that almost half of the 3-year-olds and about 70% of the 4-year-olds were able to pick out cards based on a three-dimensional description (shape, colour, and size). This was surprising because previous research shows that children find it hard to think about something in two ways one after the other until they are about 4.5 years old, and the only research that looked at coordinating several dimensions simultaneously found that even 6-year-olds perform at chance (i.e., they are basically guessing).

Why did the children in our sample did so much better? One possible explanation is that they are really smart kids. That is, that the sample we collected is not representative of children in general. But, remember I said we ran a bunch of other tasks? We also ran two standardized tests to measure vocabulary and non-verbal IQ, and the kids in our sample scored as expected in those measures. The kids in our sample did score higher than previously reported on other measures of cognitive flexibility, so we do need to replicate this work with a different sample to see if it was fluke or is it actually that children can think of something in three ways simultaneously much earlier than we previously thought.

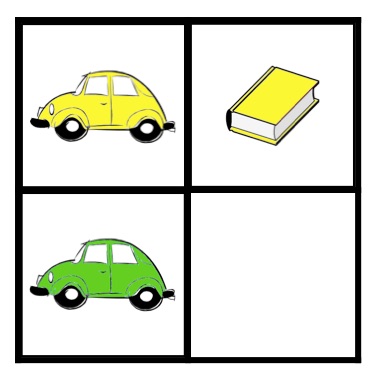

The other explanation, if this was not a fluke, comes down to the task itself. In previous works, researchers used tasks that required children first to decide what the relevant dimensions are, and then to coordinate these dimensions. What we did was to remove the requirement to decide about the relevant dimensions. So, for example, in previous work children were given a matrix like the one in the picture below, and were asked what goes in the empty cell. Children had to first figure out that the two top items are the same colour, so that we are looking for an item that is the same colour as the one on the bottom (i.e., green), and also they had to figure out that the two columns differ in shape, so that we are looking for a book to go with the book in the top row, and only then combine it together to say we are looking for a green book. So what we did is we left the part of combining together but we removed the part where they have to figure out the dimensions. So we tell them, we are looking for the small red circles. You might say, hang on, that makes the task a lot easier. Which is exactly right. But the part we took out wasn’t cognitive flexibility, it was abstraction (the ability to extract features based on visual or conceptual similarity), which is a whole different skill.

What It Means

Well, it’s not one of those grand projects. This is a project about a specific skill in a limited age group. We do not claim that this is a game-changer. By the way, very little research is—most research is just plodding along, getting a clearer and clearer picture of the world around us, bit by bit. What it does mean is that we have underestimated preschoolers’ concurrent cognitive flexibility skills because we were using tasks that were not suitable for the age group we were testing. Now, that we have a new task that is suitable for preschoolers, we can start looking at interesting questions such as: What makes some kids good at this and some kids not so good? What helps kids succeed on tasks like this one? Can we diagnose the children who are having particular difficulties with this skill and help them early to catch up? All of these are questions that we could not have answered before, because we had no way of measuring this skill in preschoolers. Now that we do, we can get on with the real work :)