When Simon Doesn’t Say: Inhibitory Control in Children

Inhibitory Control? What’s that?

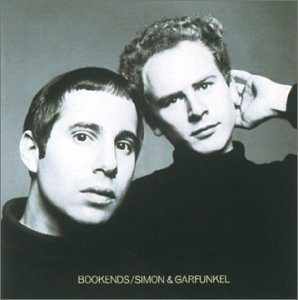

You know the game Simon Says, right? It’s when the leader gives instructions such as “touch your nose”, or “hop on one leg”. The twist is, if the direction is preceded by the phrase “Simon says” (as in, “Simon says touch your nose”), you are supposed to follow it. When the instruction is NOT preceded by this phrase, you are supposed to NOT follow it. Typically 4-year-olds find it hilarious, especially if you do a few Simon Says turns and then follow it up with a Simon Doesn’t Say turn. The ability to hold back and not follow the instruction is called inhibitory control.

A Tale of Two Inhibitions

There are two types of inhibitory control. The first type is the ability to delay a response until a suitable time arrives. This is very much the “waiting your turn” skill – you delay whatever it is you want to do until it is appropriate to actually do it. The marshmallow task is measuring inhibitory delay, and as I mentioned last week, we can see the implications of individual differences in response delay resonating throughout our lives.

The second type of inhibitory control is the ability to replace a response that is no longer appropriate with a different response. Did you ever get lost in thought while driving, and found yourself driving to your old work place instead of the new one, or to your home instead of the grocery store? That example is inhibitory control-conflict (or lack thereof) in action. Executive Functions in general, and inhibitory control particularly, keep us from doing the automatic thing whenever necessary.

Stable and Significant

Individual differences in inhibitory control skills are fairly stable. That means that the kids who are good at it when they are toddlers are more likely to be good when they are in elementary school, and the toddlers who are not so good at it are more likely to be less good at it later on. Inhibitory control skills play a role in externalizing problems (behaviours like lying and physically hurting other children), as well as in academic achievements (including math, literacy, and school readiness). In fact, a study that followed children for 30 years found that children with higher inhibitory control skills grew up to be healthier, richer, and happier adults than children with lower inhibitory control skills.

Can We Train Inhibitory Control?

The short answer is yes. Several programs showed gains in Executive Functions in general, and in inhibitory control particularly. However, the change might not be dramatic. Children who show the poorest Executive Functions performance are the ones who benefit the most from training programs. That said, it had been argued that, because inhibitory control has such pervasive implications, every little bit helps.

Do your kids like to play Simon Says?