Stretching the Mind

As promised, this post is about the most fascinating (I think) process that is typically included in Executive Functions: Cognitive Flexibility.

What is Cognitive Flexibility?

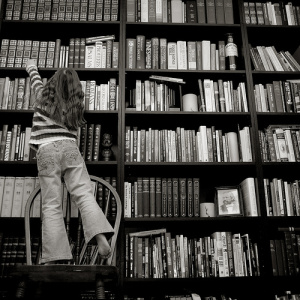

Cognitive flexibility is the ability to think about something in more than one way. For example, the child in the picture is thinking about the chair not as something to sit on (the original function), but as something to help her reach a higher shelf. This is a skill that plays an important role in problem solving (such as analogies – these problems are considered a measure of intelligence) and creativity (thinking about something in new ways, making connections between things that don’t seem to have a connection between them).

Consecutive Cognitive Flexibility (Switching)

In most research that looks at the development of cognitive flexibility in preschool-age children, researchers measure cognitive flexibility as the ability to switch between two dimensions. So, a very well-used task to measure cognitive flexibility in preschoolers gets kids to sort cards first according to colour, and then according to shape. These are the same cards, say, blue boats and red rabbits. So in order to sort them according to shape, children have to stop thinking about the cards in terms of colour (blue ones and red ones) and start thinking about them in terms of shape (boats and rabbits). Turns out that preschoolers are pretty terrible at this: most 3-year-olds and about half of the 4-year-olds reported in the literature are unable to switch, and keep sorting the cards according to the “old” dimension.

Concurrent Cognitive Flexibility (Simultaneous)

Another way to think about cognitive flexibility, however, is as a simultaneous process. This would entail thinking about a toy, for example, both as a red one and as a car at the same time (so, a red car). This is often considered to be a harder task than thinking about two dimensions consecutively (switching), and there are no tasks that measure this process in preschoolers. Which is where my research comes in.

In a study I will be presenting next week at a conference, we looked at preschoolers’ performance on a concurrent cognitive flexibility task. This task is based on the matrix completion task, which is used to measure concurrent cognitive flexibility in 7-year-olds. In this task, there is a board with three pictures, and the child is asked to “finish” the board with a fourth picture (see the picture below, honestly, in this case the picture is worth about 730 words). The most recent study that did this found that about half the 7-year-olds succeeded in this task. We made some minor changes to this task, and gave it to preschoolers. In our sample, about half the 4- and 5-year-olds succeeded.

What We Can Learn

Until now, no one even studied concurrent cognitive flexibility in preschoolers. Using our matrix completion task (and other tasks we have developed and can talk about later on), we can measure this skill. And when you can measure something, you can study it. So now comes the exciting part: studying the way this skill develops, looking at what causes children to do better or worse, and looking into ways to help children master this skill.

I would love to hear stories about flexibility in your kids (or kids you know). Seriously, tell me about that one time that your kid discovered that other people don’t call you “mommy” or “daddy” and realized that you actually have a name, stuff like that.